Several status quo situations continue to prevail around the world, including between China and the United States. The status quo is the accepted political term for unresolved global crises, most of which date back to the Second World War. In essence, it means that there is a more or less tacit agreement between rival powers to keep the crises in question frozen. The Korean peninsula, the Taiwan Strait and Western Sahara are just a few examples of these frozen or latent conflicts. Until recently, the Palestinian question also fell into this category.

To resolve these crises on stand-by, whose eruption is likely to jeopardize regional and even global security (as demonstrated by the ongoing conflagration in the Palestinian territories), China advocates recourse to international law, the fruit of historical realities and consensus, i.e. resolving the status quo by legal means. The United States, on the other hand, seeks to short-circuit legal procedures, including those of the United Nations, in order to unilaterally impose new geopolitical realities through the use of force. The accusatory inversion – the political language of coercion used by the White House – must not be misleading.

Thus, at the dawn of the 21st century, one of Washington’s objectives in its strategy to contain Beijing is to replace status quo situations, which are characteristic of a certain balance of power, with de facto situations, which would be favorable to Washington. In defiance of international law and the interests of the other major powers. This is precisely the situation prevailing today all-around China, and particularly on the Korean peninsula.

Raising the military stakes

Judging by its increasingly militarized hostility in the North-East Asian region, the US is seeking to undermine the geostrategic interests of China and Russia by gradually imposing a new balance of power, far removed from the status quo hitherto prevailing, and from any prospect of conflict resolution.

The Korean peninsula is a case in point, where North Korea has unwittingly become a cornerstone of the US strategy to contain Beijing. In addition to hindering China’s peaceful development, Washington’s aim is to curb the Sino-Russian economic partnership in North-East Asia, and in particular Moscow and Beijing’s budding strategy for exploiting Arctic Sea routes.

To hinder these multi-pronged Sino-Russian development projects, Washington is pursuing a strategy of escalation, which consists of fanning the flames of discord between the two Koreas, intensifying Pyongyang’s diplomatic isolation, and strengthening the US military presence in the East China Sea and Sea of Japan. It is in the light of these geopolitical rivalries that we must understand the US-South Korean military provocations vis-à-vis Pyongyang, but also the formation of informal military alliances, which are increasingly resembling an Asian NATO. These maneuvers on the Korean peninsula have reached a milestone with the trilateral military partnership between the US and China’s and Russia’s next-door neighbors, South Korea and Japan.

America’s alleged concern about a nuclearized Korean peninsula is clearly a pretext designed to lend a semblance of legitimacy to Washington’s warmongering on China and Russia’s eastern doorstep. For proof of this, we need only think of the unconditional American support for Israel, a nuclear power on the quiet, or for Australia within the framework of the AUKUS, or even the American threats to equip South Korea with nuclear weapons.

The real challenge for Washington is to bury the status quo that has prevailed between the two Koreas since the 1953 armistice and the various reunification projects that followed, in order to justify its military expansion around its geopolitical adversaries China and Russia. North Korea’s strategic geographic position (along with South Korea and Japan) has been integrated into the United States’ Indo-Pacific strategy as a tool enabling Washington to contain Beijing and Moscow in North-East Asia.

The effects of Washington’s de facto policy

In any case, the growing militarization of the Korean peninsula has not distracted China and Russia from their plans to cooperate on security, economic and development issues. Moreover, far from ostracizing North Korea as Washington demanded, Beijing and Moscow have made it the cornerstone of their regional development strategy. So much so, in fact, that a trilateral strategic partnership between China, Russia and North Korea appears to be the answer to the trilateral military partnership between the United States, Japan and South Korea.

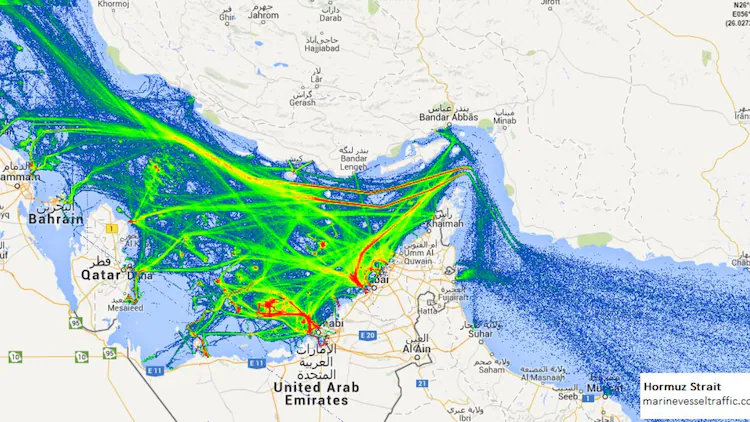

Beijing, Moscow and Pyongyang, for example, are gradually moving towards a project to develop the Tumen River – the junction between China, North Korea and Russia – with the aim of developing river and sea communications on a regional scale. Such a development would also be of major geopolitical importance for Beijing, as it would guarantee it access to the Sea of Japan. Clearly, the geographical proximity between the three partners is a key asset, enabling them to resist more effectively the drastic sanctions imposed on Moscow and Pyongyang by the United States and EU countries. As for the planned development of Arctic Sea routes, this would avoid the tensions and risks surrounding the Suez Canal, while cutting journey times to Europe.

For the time being, then, the American strategy of abandoning the status quo through an arms race on the Korean peninsula has not achieved the desired results. It has not succeeded in isolating Pyongyang diplomatically, nor has it prevented intra-regional cooperation – including security cooperation – between the three neighbors, or their extra-regional development plans. At the very least, this observation makes it clear that the status quo and the de facto do not have the same implications. Whereas the former can claim a certain legitimacy, implicitly accepted by the forces involved, the latter is a fait accompli – and lasts only as long as it is not contested by rival geopolitical forces.

In this instance, and despite the attributes of power reflected in the over-militarization of North-East Asia, the United States finds itself in an uncomfortable position, seeing with its own eyes that its military might alone no longer allows it to preside over the fate of the world as it sees fit. Moreover, in the current global context, where seismic upheavals are following one another with vertiginous acceleration, it is easy to see – even for the most staunchly Atlanticist Asian leaders – that betting their people’s future on a worn-out American hegemon miraculously rising from its ashes in the face of emerging Eurasia is a reckless risk.

Tito Ben Saba – Geopolitical consultant and analyst, especially for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”.

Source: New Eastern Outlook