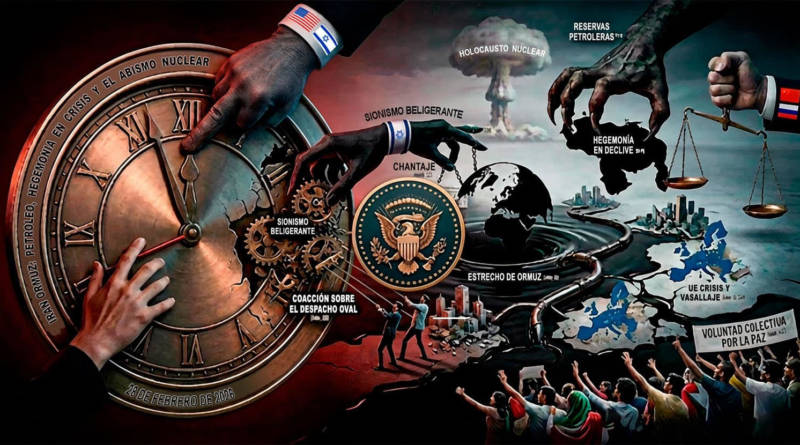

In line with the American strategy of “divide and rule”, characteristic of US hegemonic aims, the objective of Washington’s Chinese strategy is to compartmentalize rival geopolitical powers by exacerbating antagonisms, with the aim of breaking down geographical continuities, economic and security partnerships, and ideological affinities between the various regional blocs.

Behind the American strategy of containing China lies the aim of preventing the Asian giant’s economic, technological and scientific development at low-energy cost. In this context, it is appropriate to look closely at Washington’s actions towards Beijing’s strategic partners, Moscow and Tehran, across the entire Eurasian space.

Breaking trans-regional geopolitical continuities

In its standoff with Beijing, the United States is pursuing a strategy of compartmentalizing the world’s major regions, denying the geopolitical interests that bind these regions together.

Several top Western leaders have claimed that the US is being dragged unwillingly into the ongoing conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East, while its main concern is to contain China’s growing power in the Indo-Pacific region.

This amounts to saying that the United States has not invested long years, fueled by artificially colored revolutions and coups d’état propelled by hundreds of millions of dollars, to provoke its geostrategic adversary Russia, through NATO and Ukraine. It also means that Washington is a stranger to the conflicts involving Israel in West Asia, and has never vetoed Israel’s countless international condemnations by various UN bodies. This amounts to saying, above all, that these two hotbeds of conflict, Europe and West Asia, have no connection whatsoever with the American strategy of containing Beijing.

These theatrics by Washington and its affiliates cannot distract Beijing from the many ramifications of American strategy in the Eurasian space. America’s aggressive policies towards Beijing, aimed at encircling the Asian giant while subjugating its neighbors, are closely linked to Washington’s political, economic and military maneuvers in the neighborhood of Moscow and Tehran.

For Washington, hindering the “independence” ambitions of its geopolitical adversaries is tantamount to breaking the geostrategic continuity between China, Russia and Iran. We are thus witnessing a multi-frontal Eurasian confrontation, stretching simultaneously from the Mediterranean to the Arabian Sea, via the South Caucasus and the Indian Ocean, and extending as far as the East China Sea.

Breaking the Russia-China partnership in the Mediterranean and Red Seas

Faithful to its history as a hegemonic power that has never imposed itself except by armed force, the United States is committed to weaving a network of military alliances, inevitably threatening, around its geopolitical adversaries, foremost among them China. This modus operandi was first applied to Russia, Beijing’s strategic partner, forcing it out of its depth, that is, beyond its borders, to defend its vital security space in Europe.

Long before the conflict in Ukraine, countless American wars in the Middle East played a major role in reshaping the world’s security architecture. Situated at the crossroads of strategic sea lanes, and riddled with American military bases, the West Asian region is forcing emerging powers into major geostrategic planning, if only to guarantee the security of their trade and supply chains, particularly energy.

Washington, which has long enjoyed economic and military prepotency in the Mediterranean and Red Seas, is now attempting to sabotage the security of its geopolitical adversaries in these two sea lanes. Having failed to prevent the establishment of Russian military bases on the Syrian and Libyan coasts, or the Chinese military base in Djibouti, the United States is now attempting to hinder the creation of a Sino-Russian security line.

The US decision to build a port in Gaza coincides with Russia’s plans to build a military base in the Libyan port city of Tobruk. At the same time, the ongoing ethnic cleansing in Gaza reflects growing American concern about Russia’s military presence in the region. As for the deadly conflict in Sudan, it is clearly helping to prevent the establishment of a Russian naval base in Port Sudan, but also to hinder Moscow’s military breakthrough on the African continent. In other words, the Sudanese conflict seems to serve Washington’s interests, since it hinders Sino-Russian naval military continuity between the Bab-Al-Mandeb Strait and the Mediterranean Sea.

However, these events did not stop Russia’s naval presence in the Red Sea, as Moscow has signed an agreement with Eritrea to build a naval base in the Dahlak Islands. This project may partly explain the repeated bombardments of the Yemeni city of Hodeida, located opposite Eritrea, by the US-led Red Sea coalition.

Admittedly, the recent signing of a naval military agreement between Turkey and Somalia, adding to the Turkish naval base in Mogadishu, may be perceived by China as a blank check for NATO expansion in the Horn of Africa, gateway to the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean. Above all, however, this signature seems to be a response to the agreement concluded a month earlier between Somaliland and Ethiopia, which was supposed to guarantee Addis Ababa access to the Red Sea (at a lower cost than the port access granted by Djibouti) and, what’s more, a naval military presence.

As things stand, Sino-Russian security continuity is only partially guaranteed on the shores of the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. This, bearing in mind that Egypt, which dominates the strategic Suez Canal, and Saudi Arabia, whose territory stretches along the Red Sea, not to mention Ethiopia, the demographic giant of the Horn of Africa, have all just joined the BRICS.

Destabilizing security in Central Asia and around Iran

The American strategy of containing Beijing does not stop with Russia: it extends to the Persian Gulf and Central Asia, where oil and gas, China’s titanic “Belt and Road” projects, and China’s commercial and economic partners – first and foremost Iran – abound.

Its geographical position to the south of the Persian Gulf and to the north of the Caspian Sea makes Tehran an essential regional power, situated at the crossroads of China, Russia and Turkey – in other words, at the crossroads of today’s major geopolitical issues.

Admittedly, Iran has no offshore military bases, but it does possess a major geostrategic asset that enables it to project its power throughout Western Asia, from the Gulf of Aden, through the Ansar Allah Houthi movement, to the Eastern Mediterranean, through the Lebanese Hezbollah and factions in Iraq and Syria – not to mention armed Palestinian factions. This “Axis of Resistance” gives Tehran strategic depth in a number of regional theaters of operation, and indirectly gives China the power to undermine Washington’s hegemonic ambitions in the region.

The NATO bloc’s plans to deploy a military presence in Armenia along the Zangezur corridor, that is, on Iran’s northern border, are naturally perceived by Tehran as an unacceptable American provocation. This Azeri-Armenian corridor is supposed to link the South Caucasus to Europe (via Turkey), but also to China (via the Caspian Sea and Central Asia). Clearly, a NATO presence would compromise the security of regional trade. Yet it is vital for China to diversify its trade routes, given Washington’s militarization of the China Sea and Indian Ocean, the sea lanes through which the majority of Chinese trade with West Asia, Africa and Europe transits.

Under the guise of securing the South Caucasus, this plan to deploy NATO on Iran’s borders also aims to strengthen Israel’s position in the Mediterranean, by diverting Iran from the ethnic cleansing underway in Gaza.

It is through the prism of these geopolitical rivalries that we need to understand the drastic sanctions imposed on Iran, US support for armed uprisings calling for regime change in the country, terrorist attacks targeting nuclear and defense sites, and even diplomatic representations. As for the armed insurrections of the separatists in Sistan-Baluchistan, they have the advantage of creating tensions on the Iranian-Pakistani border, not far from the strategic Strait of Hormuz, but also of hindering the implementation of the economic corridor linking Pakistan to the Chinese region of Xinjiang. This trade corridor is of the utmost importance, as it would enable China to bypass American provocations in the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean, and save time by gaining direct access to the Gulf of Oman.

Like Iran and Russia, China has not escaped American methods of coercion: political, economic and military. These actions have reached such a level of hostility that the United States is even seeking to create tensions around the Strait of Malacca, vital to Beijing.

For the moment, Washington is compulsively pursuing the militarization of the entire Indo-Pacific region, sometimes threatening to equip South Korea with nuclear weapons, sometimes announcing the extension of the AUKUS to other countries in the region, or the reinforcement of American bases and troops. In this respect, the declarations of certain regional political figures, such as Shinzō Abe’s former special advisor, raise questions: rarely have we seen citizens so proud to see their country lose its sovereignty. But there are also clear-sighted voices, such as that of former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, for whom “The Americans are the ones pushing the Philippine government to go out there and find a quarrel and eventually maybe start a war”.

In any case, Washington has deployed considerable resources to deprive China of its logistical and security support, and sabotage its global architecture of cooperation. Seeing its position threatened by Beijing’s multi-continental power projections, Washington is seeking to hinder the New Silk Road projects, the strengthening of the SCO and BRICS, the adjustment of the international order to the interests of the Global South, as well as the ongoing process of de-dollarization.

By responding to these major geostrategic challenges in an exclusively hawkish manner, eschewing all diplomatic avenues and disdaining the legitimate concerns of Moscow, Tehran and Beijing, the United States paradoxically appears very weakened, behind the times, and short on imagination for renewing its place in the world. An observation that EU leaders should ponder.

Tito Ben Saba – Geopolitical consultant and analyst, especially for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”.

Source: New Eastern Outlook